In this article, we discuss the foundations of early literacy development among children. I have defined early literacy development in this article.

Most people, including parents and teachers think that teaching early literacy skills hinges only on providing reading and writing materials such as literacy books, pencils, and other resources that children need to learn reading and writing.

Literacy teaching is not only about using the best strategies but also consist in understanding the pillars of literacy development.

So, parents and teachers who miss the mark accumulate materials for children to create a supportive literacy environment.

This is commendable but there are other things we need to pay attention to. It is important to establish the foundations of literacy and examine how they help in the development of literacy.

In the early literacy concept, literacy learning, and acquisition is seen as a continuum which begins way before birth and continues until children can read in a conventional way (Kaunda, 2022; Spedding et al., 2007).

Literacy development is anchored in three major dimensions of development which are seen as foundational to the development of literacy.

These include physical motor development, language development and cognitive development. Let’s look at these in the following sections.

Physical motor development and literacy development

Physical mortar development is the development of small muscles or fine motor and maturation of the brain.

There are several ways in which this form of development affects literacy development in children. This dimension of growth affects ‘children’s ability to manipulate writing tools and to focus their eyes on printed material’ (Griffith et al., 2008, p. 5).

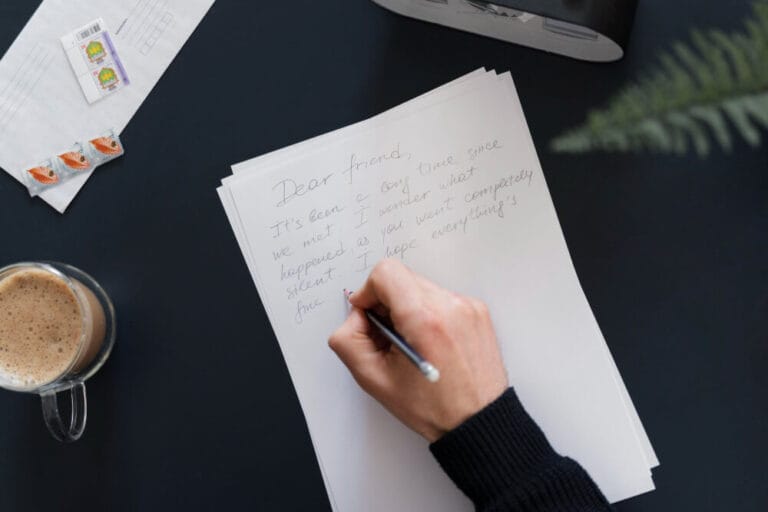

To write conventionally, children must be able to have control over eye-hand coordination. Hand control is important for keeping the paper still and for controlling the writing tool.

Children vary in terms of the age at which they grasp a pencil in a mature way. Many children struggle but by age four, eye-hand coordination is sufficiently developed in most children for easy writing and drawing (Suggate et al., 2018).

Teachers and parents can help children to develop control over paper and pencil by giving them simple exercises such as pinching, tearing paper and picking small objects which require the use of two or three fingers.

Language and literacy development

There is an intricate relationship between language and literacy development. In fact, Mkandawire (2018) writes an article where he defines literacy and looks its relationship with literacy.

There are different ways in which language supports literacy development. Supportive communicative interactions that occur in daily routines of home are important for language development.

Such interactions may include conversations on a trip to the market, during a meal, while cooking in the kitchen or while in the garage. Strengthening language development has an effect on literacy development because language development is precursory to literacy development (Michael, 2013).

The relationship that exist between literacy and language is not very clear but there is universal agreement in literature that literacy is influenced by language (Communities for Children, 2015).

Some scholars have argued that early literacy and language development start in the first 3 years while others have argued that language literacy development in the first 6 years but what studies have revealed is that children’s development of vocabulary is believed to happen during preschool years.

However, current studies have shown that vocabulary acquisition could begin before birth (Kaunda, 2022).

Wildová and Kropáčková (2015) have established a link between ‘the level of a child’s speaking development, the extent of his or her vocabulary, the ability to communicate, to listen, to articulate correctly to the level of literacy development’ (p. 879).

Other scholars have added that variations that have been observed in reading in children in the preschool years are partly as a result of variations in oral language skills as phonological skills or speech sounds are seen to be important for beginning to decode print (Hulme et al., 2015).

Oral language helps in reading comprehension and reading accuracy skills in later lower primary grades. Variations in memory vocabulary and verbal memory form part of important predictors of reading and spelling accuracy (Serpell, 2014).

Kennedy et al. (2012) argue that the role that oral language perform can be seen in two ways. When oral language is looked at as a skill possessed by a child, it performs such roles as supporting comprehension skills and the development of phonological processes.

But when oral language is looked at as a context of learning and practicing literacy skills, it establishes the role of the caregiver or the teacher in promoting high levels of cognitive interaction.

Language plays the role of the mediator between literacy acquisition and the acquirer. Parents and teachers use language as a tool for mediating and negotiating literacy.

Oral language and literacy development are sharpened at home. In cases where the home language and the school language differ, children from such homes require extra support in order to build their oral language skills (Brown, 2014).

Studies in bilingual communities have indicated that literacy skills learnt in one language transfer to another language (Tambulukani, 2015). Literacy acquisition is therefore faster if instructed in a home language.

Much of the learning which occurs in the home is developmental. In the development stage, literacy competence begins with familial experiences. Children develop behaviors, knowledge, and skills through multimodal means.

Cognitive development and literacy development

Before I talk about how cognitive development affects literacy, let me define cognitive development and establish a connection between language and cognitive development.

Gauvain and Richert (2016) argue that ‘cognitive development is the process by which human beings acquire, organize, and learn to use knowledge.’ Therefore, cognitive development in children is the development of knowledge, skills, problem solving and dispositions, which help them to think about and understand the world around them.

To fully acquire skills and understand the world around them, children need language. Language is regarded as a tool for children’s interactions with the world, learning about the world, and solving problems.

Oral language is a symbol system that represents actual objects or ideas in the world. Written language turns oral language into a second order symbol system (Griffith et al., 2008).

This happens through a process of symbolic or representational thinking. It is this form of thought that has a major bearing on literacy development.

Vygotsky, in his Sociocultural theory made a connection between children’s symbolic thought and written language as ‘second order symbolism which gradually becomes direct symbolism’ because written language, a second symbol turns oral language into a second symbol.

He suggested that the preschool years are the ideal time for a ‘natural’ and meaningful introduction to learning written language. His view is that ‘symbolic representation in play is essentially a particular form of speech at an earlier stage, one which leads directly to written language.

As children understand the world and use abstraction, they can apply abstraction to reading and wring.

Summary

From the discussion above, it is important for teachers and parents to help children develop their mortar skills.

Mortar skills are important in physical manipulation of writing and reading tools. Language development is another important factor in literacy development.

Lastly, cognitive development is important in helping children use abstract forms of representational skills for literacy development.

References

Brown, C. S. (2014). Language and literacy development in the early years: foundational skills that support emergent readers. Language and Literacy Spectrum, 24, 35-49. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1034914

Communities for Children. (2015). Early years literacy and language development strategy for Bendigo. Communities for Children Bendigo.

Gauvain, M., & Richert, R. (2016). Cognitive Development. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Mental Health (Second Edition) (pp. 317-323). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00059-8

Griffith, P. L., Beach, S. A., Ruan, J., & Dunn, A. L. (2008). Literacy for young children: A guide for early childhood educators. SAGE Publications Inc.

Hulme, C., Nash, H. M., Gooch, D., Lervåg, A., & Snowling, M. J. (2015). The foundations of literacy development in children at familial risk of dyslexia. Psychological Science, 26(12), 1877–1886.

Kaunda, R. L. (2022). Developing children’s early literacy in Zambian preschools: A postcolonial exploration of preschool teachers’ beliefs, understandings and practices [Thesis, The University of Newcatle]. Newcastle.

Kennedy, E., Dunphy, E., Dwyer, B., Hayes, G., McPhillips, T., Marsh, J., O’Connor, M., & Shiel, G. (2012). Literacy in carly childhoodand primary education (3-8 years). NCCA. www.ncca.ie

Michael, S. (2013). Supporting literacy development for young children through home and school connections. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 42(2), 29-37.

Mkandawire, S. B. (2018). Literacy versus Language: Exploring their Similarities and Differences. Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, 2(1), 37-55.

Serpell, R. (2014). Promotion of literacy in Sub-Sahara Africa: goals and prospects of CALPOSA at the University of Zambia [Article]. Human Technology, 10(1), 22-38. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sxi&AN=97006714&site=ehost-live

Spedding, S., Harkins, J., Makin, L., & Whiteman, P. (2007). Investigating children’s early literacy learning in family and community contexts: Review of the related literature (Learning Together Research Program Final Report, Issue. D. o. E. a. C. s. S. Early Childhood and Statewide Services. https://www.education.sa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net691/f/learning_together_lit_review.pdf

Suggate, S., Pufke, E., & Stoeger, H. (2018). Do fine motor skills contribute to early reading development? Journal of Research in Reading, 41(1), 1-9.

Tambulukani, G. K. (2015). Fisrt language teaching of initial reading: blessing or curse for the Zambian children under Primary Reading Programme? [PhD Thesis, University of Zambia]. Lusaka, Zambia.

Wildová, R., & Kropáčková, J. (2015). Early childhood pre-reading literacy development. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191 (2015), 878 – 883.